Like any in-person event, film festivals are hard to realize. In a normal year, they’re exhausting to organize; they’re expensive to produce. In a pandemic? They’re something else entirely.

But what if that “something else entirely” sparks an exciting new era for the future of film programming?

On September 20th, Ian Gailer and a small team of passionate cinephiles wrapped the 10th anniversary of the Festival de Cinéma de la ville de Québec (FCVQ; the Quebec City Film Festival). Gailer, the festival director, wasn’t just putting on a five-day film festival in the middle of a pandemic — he was doing so as the father of a newborn second child.

Full disclosure: I did a small amount of scouting for Gailer and programming director Laura Rohard this year, but I certainly wasn’t privy to the conversations about how the festival would actually look and feel. So, on September 16th, as I sat down to watch the world premiere of Pascal Plante’s originally Cannes-bound Nadia, Butterfly from my couch, I was able to enjoy exactly what Gailer and co. had been spending all summer planning.

The result? eFCVQ.

What was eFCVQ? Think three simulcast livestreams — each named after the Quebec City venues they were duplicating virtually — all with distinct programming synced to physical events happening at the same time. Didn’t have a hard ticket to a film at the Fine Arts museum? You could just watch online.

“We really loved the idea of keeping the linearity of a film festival — we really enjoy schedules and serendipity,” Gailer says. “A livestream with something that is really on time was a way for us to bring people together — to share an experience at the same time.”

Without an on-demand option, eFCVQ subsequently created FOMO. If you weren’t at your computer or TV when a film was starting, well — tant pis.

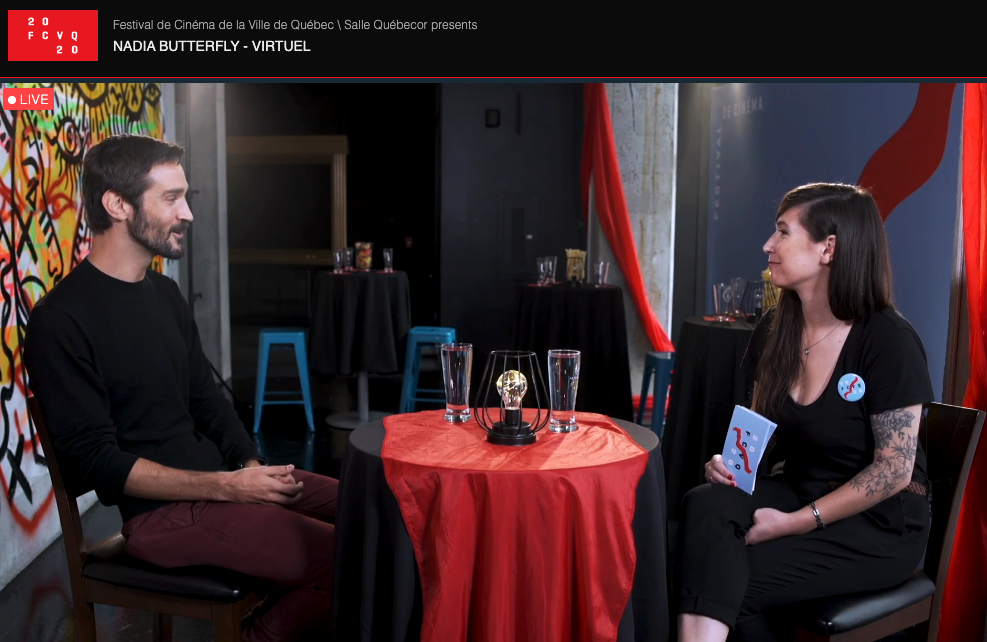

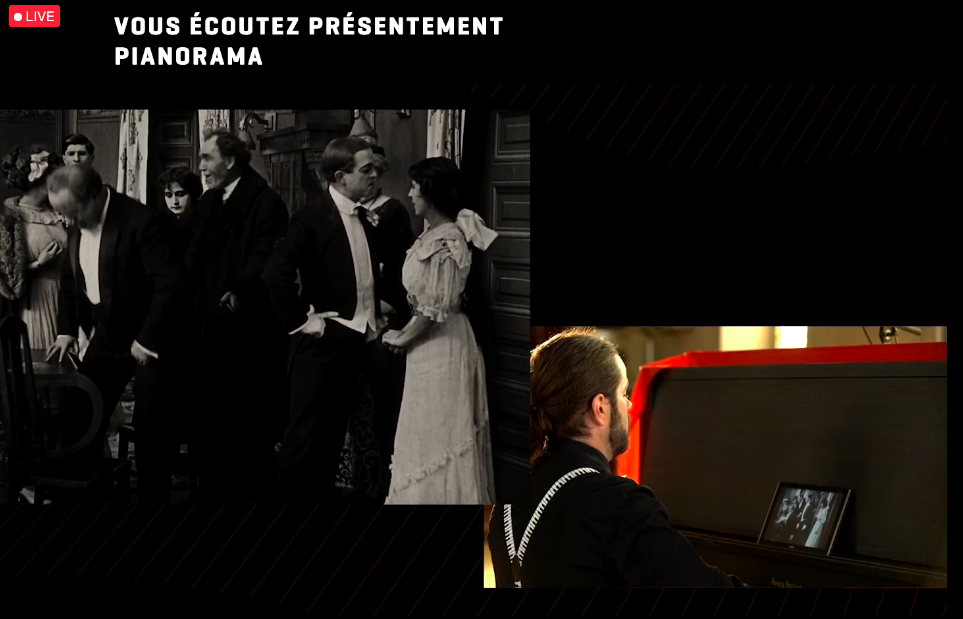

This always-on livestream model lent itself to genuine surprises, too. Before and after films, eFCVQ had vibrant in-person interviews with a colourful set, a live chat for people to discuss the festival as it unfolded, and even side-bar vignettes to fill airtime. Imagine a film festival television network: What would that look like? When I saw a local pianist play a ditty to an old-timey silent film before Nadia, Butterfly, I realized the digital film festival had tons of potential.

Pascal Plante ( Nadia, Butterfly) speaks with FCVQ programming director Laura Rohard.

Pianorama pre-show.

“Festivals are all about celebration,” says Gailer. “We worked to be sure [eFCVQ] was positive and uplifting. It’s easy to sing in a somber or dire tone, but we should never tread this way. Because passion must be shared with enthusiasm — not with regret.”

The alternative to always-on? On-demand, which the 2020 edition of the Toronto International Film Festival (and so many other festivals) partly opted for. Given its size and scope, TIFF’s pivot to on-demand rentals via their TIFF Bell Digital Cinema platform was, in many ways, a gargantuan effort — but ultimately an incredible one. More importantly, it leveled the playing field for an infinitely more accessible event.

I can’t speak for others, but by the end of the festival (September 20th), it was clear: my TIFF 2020 experience had no mad dashes. No last-minute stresses. No ticket-related headaches. I get that can sometimes be part of the fun, but watching some of the biggest films of the year (Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland, the People’s Choice Award winner, is as good as everyone says it is) was undeniably easy. There was no need to camp out in a rush line, linger in some virtual queue, or luck into a hard ticket from a friend.

It all just worked — and the streams were sturdy and lightning fast. In fact, keeping with Bell’s cheeky creative about “watching TIFF anywhere,” I even inaugurated my first annual “Topside Internet Film Festival,” which saw a few friends gathering on my rooftop — leading to, strangely, some of the best TIFF memories I’ve ever had.

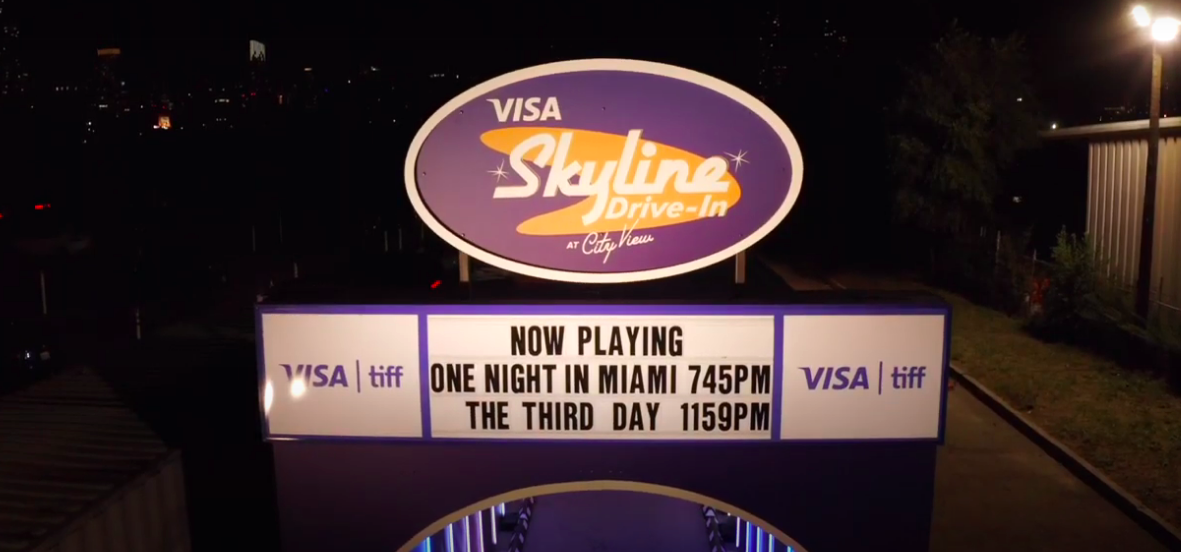

But that’s just it: “Memorable” has to be the word for TIFF 2020, and for so many events this year. Complementing the virtual screenings were incredible moments of in-person celebration — moments that were truly special. From all accounts, the drive-in (!) screening of Spike Lee’s American Utopia was a honkin’ good time. Indeed, in the Toronto Star, Cameron Bailey describes a “magical atmosphere” of the open-air cinema. No, it wasn’t the same as last year; no, it wasn’t the celeb-spotting, movie-loving frenzy that has since dominated downtown every September. But it was certainly still TIFF — and it was certainly still awesome.

TIFF’s Visa Skyline drive-in.

“Audiences and industry members were very satisfied with what TIFF was able to pull off,” says Ravi Srinivasan, one of TIFF’s international programmers. “It was extremely successful from my vantage point.”

Given the precarious nature of any physical space right now, these are words that are great to hear — especially as Srinivasan’s vantage point was one from the stage.

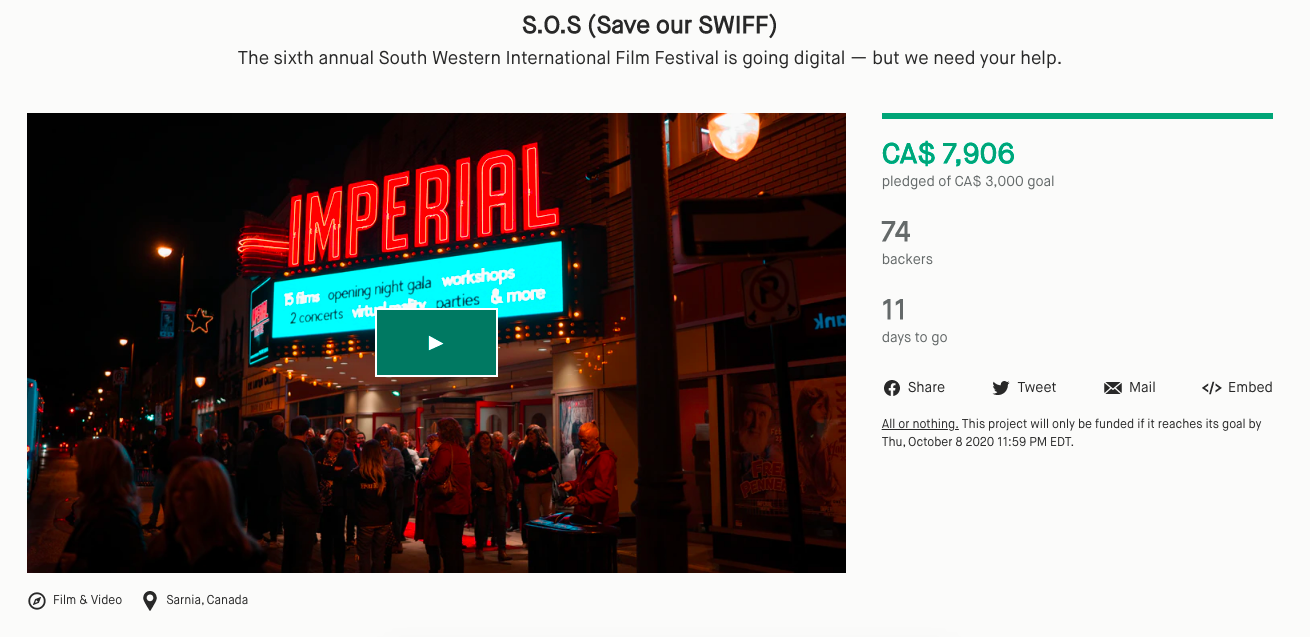

On November 19th, however, Srinivasan will be pivoting to his own digital model for SWIFF 6 (the sixth annual South Western International Film Festival), Srinivasan’s labour of love that normally brings the world of film to his hometown of Sarnia, Ontario’s Imperial Theatre — a theatre that has, sadly, since had to close.

With no cinema to activate, SWIFF 6 was in danger of cancelling outright — until the people of Sarnia stepped up for the “Save our SWIFF” Kickstarter campaign, which has, wonderfully, more than doubled its financial goal, reinforcing just how cherished this event is to Sarnia-Lambton locals. By contributing to the campaign, SWIFF backers can look forward to a satisfying movie night — or an afternoon masterclass with industry experts — all at home, accompanied by food and drink from some of Sarnia’s brightest businesses, effectively bridging the digital and physical gap with safety, comfort, and good eats. And that’s really cool.

$7,906 (as of writing) is a lot higher than $3,000.

“We made the decision in early August to commit to an online version,” says Srinivasan, the festival director. He explains he spoke with fellow leaders at festivals in Vancouver, Calgary, and even Halifax before settling on an on-demand platform. “It’s basically a completely new challenge for everyone involved.“

“Getting ahead of everything you need to do digitally is key,” Srinivasan adds. “There’s lots of tech troubleshooting beforehand, but it’s also about realizing that you can’t expect people to be less busy during a pandemic — that’s just not realistic.”

Physical losses and tech frustrations aside, there are legitimate gains made from eFCVQ, TIFF Bell Digital Cinema, and SWIFF’s crowdfunding success. If the pandemic ended tomorrow, both Srinivasan and Gailer suggest the innovative digital offerings festivals have dreamt up with this year are viable to stick around — even in years that are, y’know, normal.

“We see this year as a prototype, not as something final,” says Gailer of eFCVQ. “We invented something that is reliable — something that could stay over the years.”

“If 2021 were to go back to normal, having a digital component will be a nice add-on,” Srinivasan says.

As Srinivasan continues to finalize programming details for SWIFF 6 (which are trickier than usual, due to distributors’ on-demand piracy concerns), he says he’s having the best luck with international films that haven’t found Canadian distribution yet — effectively demonstrating the SWIFF motto of “seeing the world.”

Which makes you think: Maybe there’s something extraordinary about SWIFF 6 — about the mid-pandemic film festival as a whole. It’s an event that’s less expected; more organic. It’s an event of genuine discovery — of greater access to all.

“I think we’re going back to a more independent level of films at festivals,” says Srinivasan. “That could be very exciting for emerging filmmakers all over the globe.”

Drive-ins, simulcasts, rooftop screenings — pandemic or not, if these pivots and newfound independence are permanent additions to your typical arts events in the future, we might be on the cusp of a genuine renaissance.

A wild one, sure — but a renaissance nonetheless.

Written for the Academy by Jake Howell